Who Remodeled A Portion Of The Versailles Gardens To Make Them More Sensitive?

A Tourism Resolution

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

001

What is a hotel?

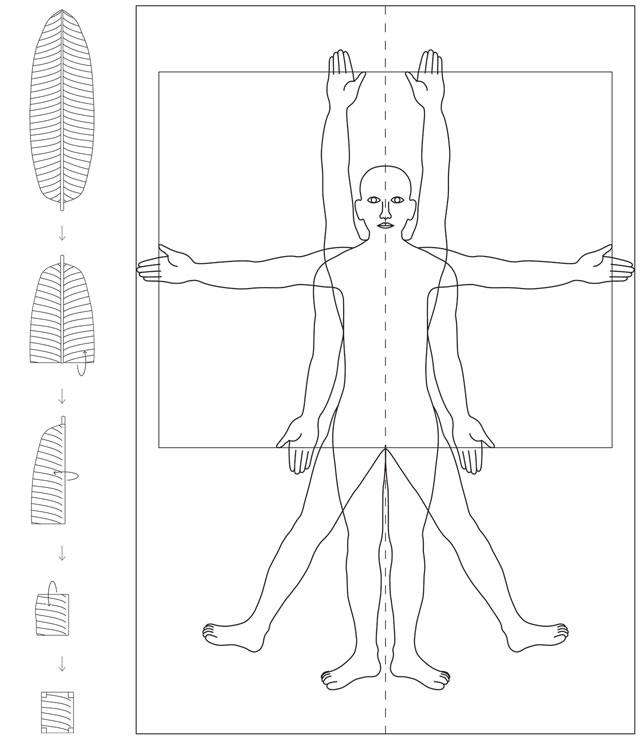

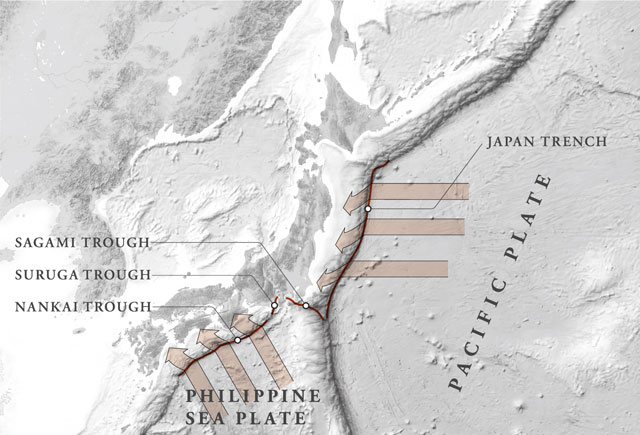

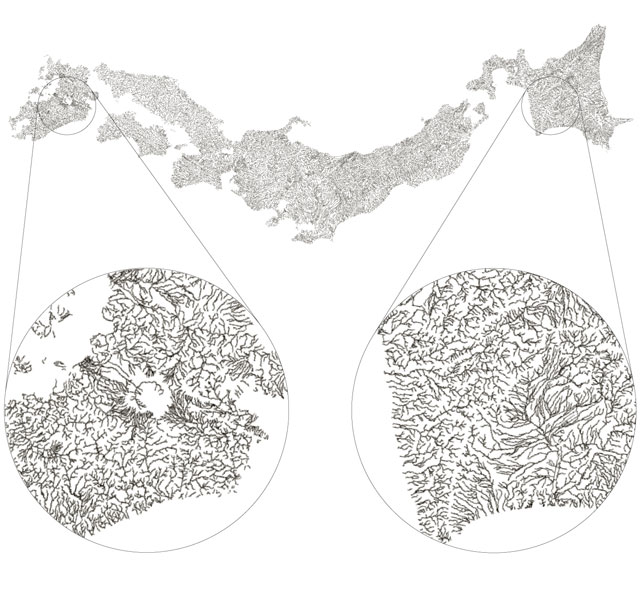

When you focus your sight on the allure of the climate and topography of the world, something that lies ahead suddenly comes into view: the hotel. Why? Because a most well done hotel is the ideal interpretation of its locality; it itself is the very topography, climate and cultural features of its setting. But why do we not just fix our eyes on nature itself? For instance, if you concentrate on the Japanese archipelago, it should be enough to express a litany of its beautiful mountains, rivers and streams. Because it is a chain of volcanic islands whose land was pushed up from the seabed, the land is steep and there is an abundance of rivers and waterfalls. Japan's seasons are diverse and rich with change; the subjects of which we could and should speak are limitless. If we are to speak without fear of being misunderstood, however, we must point out that there is nature everywhere in the world. We are truly inspired and impressed when we find the vestiges of a long period of human habitation in one place and when we see, preserved in some astounding form, the products of wisdom gained by unbroken inheritance. Specifically, we sense from the sight of a line of villages and houses the condensation of an ingenuity, wisdom and aesthetics based on the unique needs of individual localities. It's because we become keenly aware of the self-respect of people who have lived their lives modestly yet tenaciously and bravely in the bosom of nature as human beings.

The heat, the cold, in fact, much of the wisdom of survival in each locality can be assessed from the appearance of the homes found there: the material and slope of the roof; the shape of the tiles; the depth of the eaves; the construction of the entrance and the size of the windows. Those are the results of having been able to survive, as well as the products of life and lives continuously connected through time. As humans, we live, building houses, installing gardens, soiling, then cleaning. That's how we lead our lives.This is why we're far more impressed with seeing how people have related and interacted with nature than with the splendor of pure nature or wilderness. However, with the spread of technology, the world is heading toward homogenization.

Regrettably, convenience and efficiency will easily transform the lifestyles that we've cultivated over hundreds of years. It's up to the people who live in each area whether they choose tradition or convenience, but the outlook is not necessarily favorable.

Convenience is not restricted to the rich. People increasingly gather in the cities, depopulating villages increasingly die out, and convenience negatively affects the countryside. Just as the contours of solitary islands are encased in massive amounts of plastic waste, along with depopulation and the deterioration of rural houses, a certain pride people once fostered in their way of life is crumbling and disappearing.

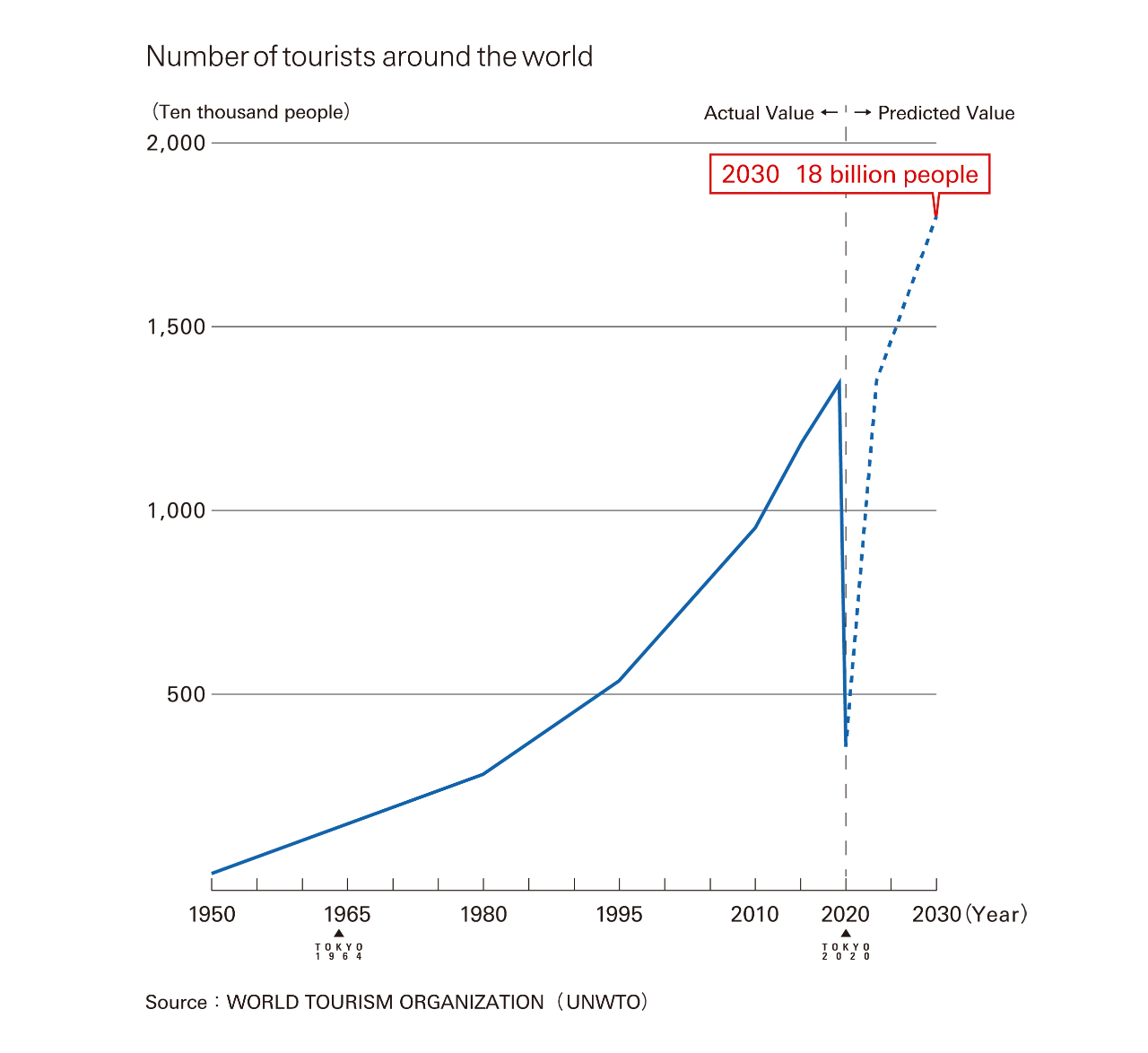

On one hand, the world is entering "the era of drift". In any one region, it is not simply the people who live there, but others, people who want to experience that area's richness and splendor, who are beginning to move there. Our values have begun to change: work, happiness, and the destination of intelligence. I feel it's likely that in this global age if we are not going to lose our pride in experiencing and appreciating the blessings of this living earth, we must transfer our interest to concern for the preservation of the environment and the cultural value that lies in the various localities themselves. The rewards of these efforts have been emerging gradually.

Today, hotels are not simply places that offer a safe place to stay and a good night's sleep and a replenishment of resilience in order to support people's travels. Instead, they are establishments for comprehending and appreciating the dormant nature, and clearly and impressively expressing it to guests, through architecture. They are also places where people will enjoy service that includes a superb harvest and preparation of the bounty of local foodstuffs.

There is no denying the fact that it is up to the hotel's carefully considered construction and layout whether we notice the comfort of the breeze of a plateau, or recognize anew the serenity of a beach or understand that the light varies depending on the location. Through hotels, perhaps along with economic development born from serving visitors, there may be a ressurection of the joys of living in that place.

People have special affection for the mountains and rivers of their hometowns. And they inevitably find the cuisine of their hometowns more delicious than that of other towns. Of course, it's good to have that special feeling towards the hometown in whose bosom one was raised. And yet, if one were to tell the world about the charms of one's hometown, perhaps it might be better to tone down one's adoration and glorification.

On one hand, the psychology of the guest is such that he will accept without question the good fortune that befalls him. So he is liable to incline both ears to the favoritism displayed in boasts about ones hometown, delight in his good luck at being able to visit, and will want to take home its foodstuffs and other products as souvenirs. It may be that the fame of most of the famous places and famous products came about as the psychology of the visitor revealed itself.

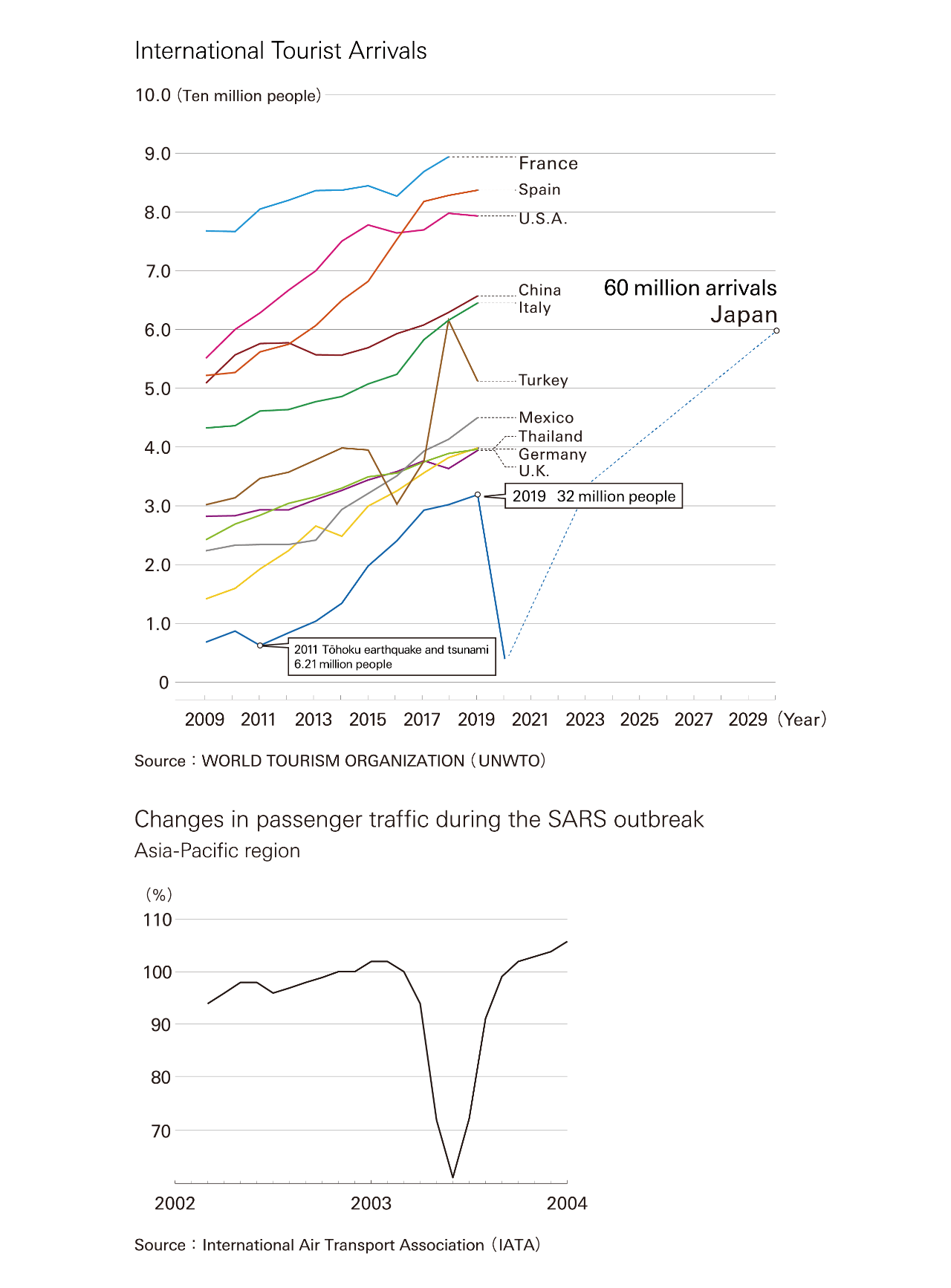

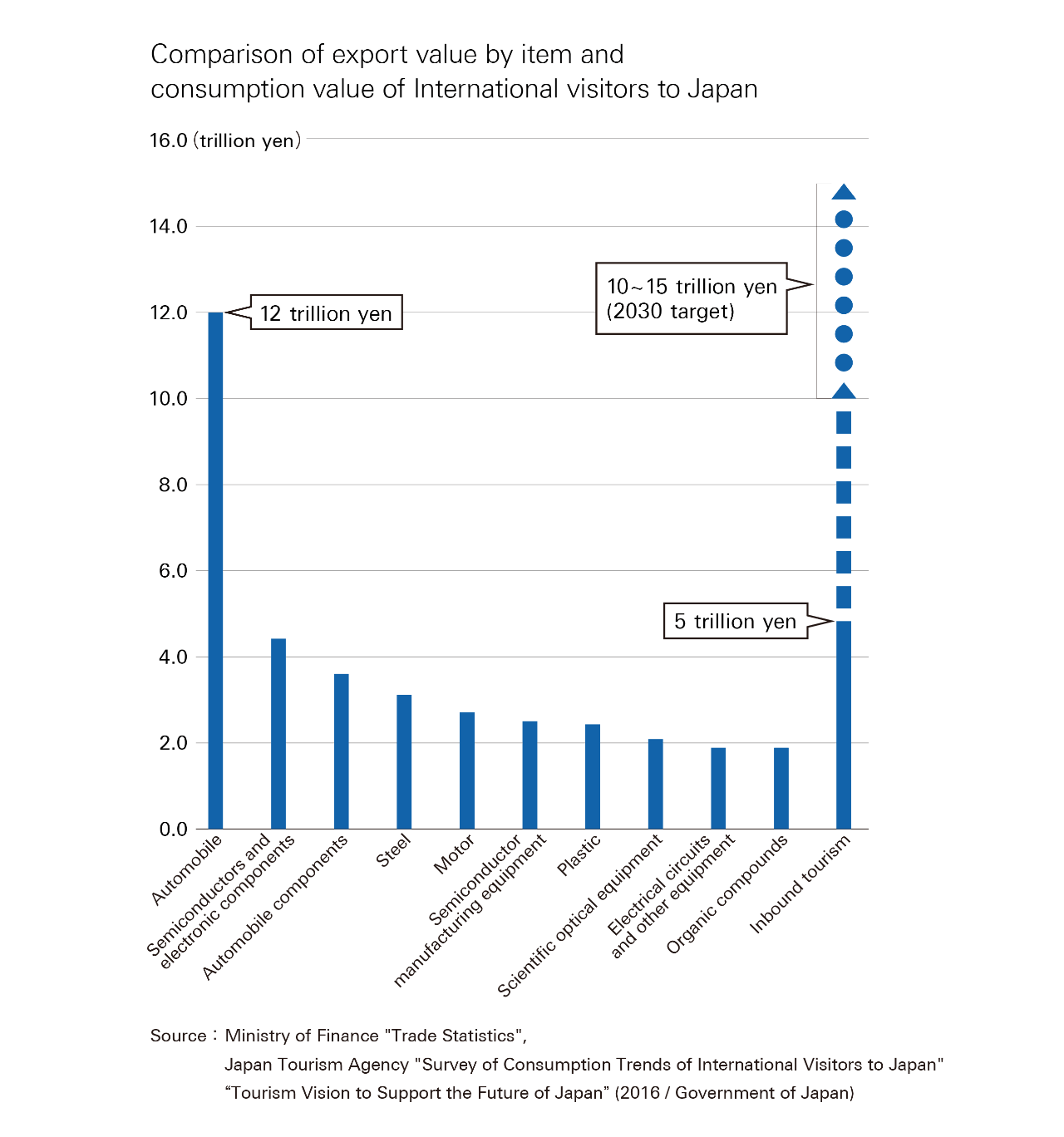

However, going forward, in thinking about industry of the future, I think it's necessary to reexamine the possibilities of tourism as a way of comprehending and delineating each region, based on a new granularity and objectivity. This is because tourism is thought to be the largest industry of the 21st century. Through manufacturing, Japan achieved postwar reconstruction, rapid economic growth and rose to a position of economic powerhouse. However, it seems that the first chapter of this legend has come to an end. And the next chapter has already begun, with our traditional culture and topography and climate as resources. This I believe.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

002

Geoffrey Bawa and his architecture

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright said that the beauty of nature is impressive as landscape only when architecture exists there as an artifact. Certainly, the existence of nature itself does not awaken us to its beauty of nature. Nature comes into its own in contraposition to the placement of architecture, a symbol of human agency. One of his masterpieces, Falling Water, is a villa straddling a waterfall. The establishment of architecture there makes nature more conspicuous than it is by virtue of the simple existence of a waterfall.

I'm writing this manuscript in a hotel called "Heritance Kandalama" near the town of Dambulla right in the middle of Sri Lanka, designed by Sri Lanka's leading architect, Geoffrey Bawa, who has been attracting attention as an influencer of Aman Resorts, known for highlighting the culture and environment of localities in which they're built.

Bawa's style is characterized by architecture as an interpretation of the surrounding nature; in his work architecture acts as an agent for the experience of light, wind and landscape. His is not particularly progressive architecture brandishing form and structure. However, I greatly admire the wonderful natural features of Sri Lanka as presented through this architecture. If we consider a hotel as an apparatus that interprets and presents the assets of nature and a region, Bawa's work is a good example.

Geoffrey Bawa was born to a wealthy family, the second of three brothers. His parents died relatively early, but, supported by some relatives, he was able to study abroad at Oxford. Therefore, I imagine that he possessed a multifaceted cultural viewpoint encompassing the West and Asia from a relatively young age. It is said that he loved Italy so much that he wanted to spend his life there. Apparently he traveled around the world in a Rolls Royce, so it seems that he was no destitute backpacker.

At 31, encouraged by a cousin who was impressed by his competence in remodeling his family home in Sri Lanka, Bawa entered Oxford and studied architecture. When he eventually returned to Sri Lanka, he began working as an architect. Although he was not prolific, from the very outset of his career his architecture has been imbued with the indivisible relationship between nature and architecture.

Heritance Kandalama is one example. Before our eyes is a large reservoir, built to secure the water supply for agricultural use. The hotel stands as if clinging to bedrock on the hill overlooking the lake, and the infinity pool is situated to appear as if extending over the lake. Visually, the edge of the pool connects with the surface of the distant lake. Because the artificial straight line of the pool's edge penetrates the organic natural landscape, visitors' experience of the surrounding nature is even more inspirational. In addition, since the bedrock has been intentionally allowed to penetrate the interior, visitors continually come in contact with the wildness of bedrock as a material. Plants flourish in tropical Sri Lanka, close to the equator. The majority of the concrete and iron building seems to be enshrouded in succulents. Therefore, it's difficult for visitors to know the entirety of this structure, so in harmony with nature is it.

I walked through Heritance Kandalama around sunrise. Before and after sunrise is a very special time of day when we celebrate a supreme quiet and delicate light. The architecture and its every space respond gracefully to the first light of day.The mirror-like pool reflects the pale ruddy sky, creating a wonderful contrast with the distant view of the rippling lake. The dawning low light projects leaf-filtered light onto the white walls. Clear light shining on fine balusters throws long, thin shadows on the floor.

In the corner of the landing of the exterior staircase a desk and chair are arranged to command a view of the lake. Sitting there, you'll naturally find yourself looking over a landscape continuing on into the distance. Framed by the architecture is a shimmering tropical rainforest scene made three dimensional in the low light. I get the feeling that I'm sharing the same joyous state of mind as the architect, who no doubt delighted in the richness of this land.

In the restaurant breakfast preparations have begun in the morning light; here we witness the plenitude of the Sri Lankan curry, the fresh vegetables, the radiant fruit and the fragrance of powerful aromatic Ceylon hanging on the breeze.

This is a land where the East India Company thrived and the British were widely involved in both trade and politics. Now it is as if the land has digested and assimilated all of that history and culture and now cordially offers its heritage to visitors as the blessings of its natural features.

This hotel, by not leaving nature alone but rather allowing for human intervention, makes nature stand out more, and splendidly assembles and presents to visitors the nature and attendant history and culture of this place. In other words, we can think of the hotel as the ideal interpretation of the natural features, traditions and foods of the region of its location.

This is an activity that produces pleasure as we, as living human beings, meet nature.

If Japan is going to move on to the next chapter, it's probably necessary to reinterpret our own country and its natural features. As we face the era of drift, there has been an increase of the numbers of visitors from abroad in almost every country; this phenomenon is in no way limited to Japan. The question is how we come to grips with this and what sort of interpretation of the natural features, history and culture of our country we can offer. I believe the result will be one of the most significant determinants of the affluence of 21st century countries.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

003

What came out of colonial rule

There is a person who, paying attention to the architecture of Geoffrey Bawa, created the form of a trip's final destination: the hotel, achieving a degree of perfection that has become a worldwide sensation: Adrian Zeccha, founder of Aman Resorts. Born in Java to a father whose Dutch forebears managed projects for the East India Company, like Bawa he understood the eye with which the west views Asia and recognized simultaneously the limits of capitalism and the potential of local culture. Sukarno, who ruled Indonesia after the colonial era, nationalized many remaining Dutch assets. Zeccha, having lost his assets and position as a member of the ruling class, relocated his base to Malaysia and Singapore and wielded his skills as a journalist for a magazine focusing on Asian art and travel. It's likely that his peculiar early life and personal history, unfolding against the background of colonialism, likely instilled the lifestyle and tastes of the world's wealthy into his business intuition.

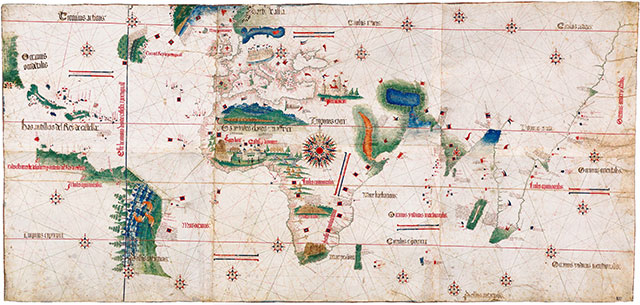

As history shows, Southeast Asia was under the colonial rule of Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, Britain, France and the United States. Both cheap labor and an array of special products such as Asian condiments, high-quality tea and cannabis that could not be obtained in the colonial nations, as well as a vast expanse of civilized pre-modern territory made up of nations with weak leadership, was a suitable frontier for capitalism. During the Age of Discovery [approximately early 15th to mid-17th centuries], Western world powers, which fully grasped the potential of this frontier, competed with one another through force to be the first to explore the globe and colonize Southeast Asia. To understand how contemporary Westerners responded to this situation, we need only observe the cultural heritage of the colonial period that remains today.

In human history, Asia is the one that had led the world's civilization, and yet the trend of modernization sent that leadership towards the West for a bit, and the popular revolution occurred in the West and civil society and capitalism took hold there first. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution, symbolized by the steam engine, welled up in Europe, and all of a sudden civilization and culture took on the condition of admiration for the West and resentment towards the East, and Western civilization, having gained predominance, swept the world. Why popular revolution and capitalism didn't erupt in the East and the West took the lead are mysteries of history, but spurred on by this fact, Western civilization, maintaining a clear predominance, crept into Asian culture as well.

Even though Western people of the time regarded and presented Asian style as novel and exotic, they did not place them in a central role, but rather advanced their own countries' styles everywhere. Architecture of the colonial period is said to be eclectic and amalgamated, but the basic tone is Western, and objects like furniture, fixtures and clothing are very localized versions of Western items. Because these Westerners hauled an opera house to the far reaches of the tropical forests of the South American Amazon, in a way, this thoroughness in creating localized versions of Western cultural artifacts was, in a sense, admirable.

In otherworldly Asia, far removed from the cultures of their own countries, against the backdrop of the riches brought forth from this place, they enjoyed the springtime of capitalism by carting in luxurious living spaces and gastronomical pleasures. That desire for such practically overflowing riches made colonial culture special. If mankind's desire is the power that improves and furthers culture, the colonies might have been a utopia of Western civilization, flourishing more brilliantly than the colonizers' original countries. The colonies were flooded with an excessive extravagance that colonists would never have experienced if confined to their own countries, and a splendor spiced with an exotic atmosphere, in contrast to the authority originating with the nobility and aristocracy.

Teach your own country's manners to the local people, dress them well in white uniforms, have them serve at superbly finished hotels and restaurants of the otherworldly tropics, and allow them to pour you first-rate wine at tables covered in white tablecloths. Sometimes even today we witness this sort of scene in the movies. It's as if the further removed from civilization, the brighter glows the extravagance.

Upon the conclusion of the Pacific War, the countries of Southeast Asia escaped colonial rule and gained independence. During this period, Geoffrey Bawa developed as an adolescent and Adrian Zeccha as a young boy. In the Sri Lanka and Indonesia of the day, what exactly did Bawa and Zeccha see? I wonder if it is this blinding potentiality that they saw in Asia's culture and natural features, identifying colonial rule in reverse perspective.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

004

The Oberoi, Bali

The very first time my heart fluttered with joy over a hotel was at the Oberoi Beach Resort, Bali. When I was 20, I'd spent two months as a backpacker wandering around Europe, the north coast of Africa, India and Pakistan, but I'd had no connection with any place that was like a resort. At one point, in my mid-20s, I decided on the spur of the moment to take a vacation, and my wife and I went to Bali. We were staying at a seaside hotel in the Kuta District, but because someone recommended the nice atmosphere of the dining situation at the next hotel over, we went to have dinner there.

Even though it was the "next hotel over", because resort hotel grounds are so spacious, and it was completely dark, we took a taxi. We were let off at the appointed location, but the area was pitch black, and we didn't see anything that looked like a hotel. All we did come across were a pair of terrifying Balinese carved sculptures that seemed to rise up out of the dark. Extremely startling because they were lit from below, it seemed, oddly, that what the sculptures were indicating was the entrance to the hotel. At that point began a stairway leading down. The taxi having sped away, abandoning us in this "otherworld" of the evening, we had no choice but to descend.

After we nervously descended the staircase, we found ourselves in front of a massive door. It was a splendidly decorated door, far oversized for the mere passing of people. As things stood, however, there was nothing we could do but open it. We emerged into a corridor much larger than we would have imagined, whose walls were decorated with intricate and stylish Balinese motifs. Thinking that we had come to a place where we really didn't belong, I felt embarrassed, and had the sensation that my feet weren't touching the ground. From there, we proceeded outside, and were guided to the bar to wait, but to this day, I cannot forget the scene we encountered outside.

As we descended towards the beach, the broad staircase continued on and on, but on both edges of every single step were placed candles, alight. This continued all the way to the edge of the property, accompanied by the blinding lights, undulating like small waves across the staircase. I got the strong sensation of goosebumps rising on my flesh.

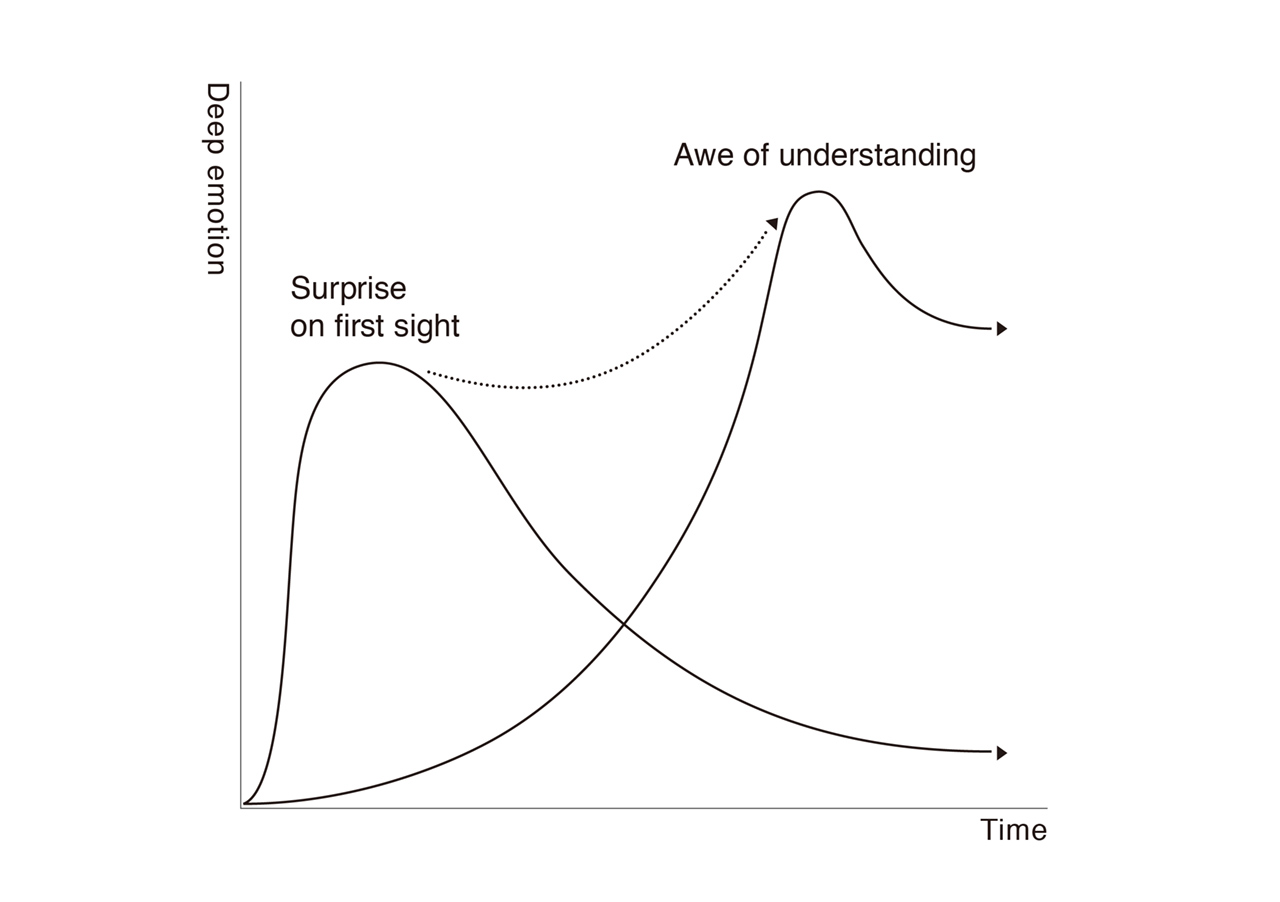

I've experienced so many journeys since then; if the person I am today were to encounter the same place, most likely I'd feel nothing special, and the Oberoi, after enduring more than thirty years in the highly competitive Bali hotel market, has probably changed. However, just like the youngster who drinks Coke for the first time, blinking through the shock of the bursting of tiny bubbles, I want to forever keep the impression somewhere in my senses: the impact of a hotel that retains the vestiges of the Dutch colonial period. And surely, I think I will never forget the deep emotions that caused those goosebumps that time.

At the bar, drinking a luscious cocktail out of a coconut shell, I immediately fell into the relaxation of the resort experience.

Culture is a fascinating thing. Even granting that colonies hold the history of exploitation caused by capitalism, the culture bred there, even after the end of the reign, does not simply vanish from the land. Even if there has been a history of arbitrary, one-sided exploitation for profit due to unequal circumstances, the pleasure created there does not only strongly influence the side on the receiving end of the luxury, but also those who provide. Perhaps discovering the local abundance as the lode of value or worth that can present in a global context the local culture, or the charms of their area's natural and spiritual features, has provided a lasting impression on the local people.

Even should a strong power from without rule, or foreign architecture based only on greed for the land bristle on the land, as long as the value or worth that manifests itself there is deeply rooted in the local culture and environment, it seems likely that the local people will inherit it as an object of pride. In Bali, where Aman Resorts initially developed hotels, that atmosphere wafts richly. High class resort hotels built with Western capital continue to devote themselves to unscrupulous practices for offering clients the environment and atmosphere of the localities in which they build. However, Adrian Zecha could predict what would happen if the side that comprehended the merits and the market of those locales developed a plan for a hotel of uncompromised quality.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

005

If China had commanded the Age of Discovery

People say that there is no "what if" in history. Certainly, history is a discipline that values facts, disallowing rash assumptions. But I'm no historian. So as long as we treat history as that which allows us to envisage the future, I prefer to pose lots of "what if" questions precisely in order to try to grasp the reality of historical facts. In addition, I wish to then create a future story based on this.

So here's one hypothesis: If Asia--or China--had dominated the Age of Discovery, achieving an industrial revolution before the West did, how would the world have been transformed?

For instance, China during the Song dynasty (960-1279) was at the vanguard of civilization in many ways. While paper was invented during a previous dynasty (Han: 206 BC - 220 AD), the Song dynasty stood out in terms of providing an environment in which everyone, regardless of lineage or pedigree, could access higher knowledge due to the publication and distribution of accumulated wisdom, arranged and organized in the form of books according to a precise management system. In addition, with a carefully organized and conducted system of proofreading and printing, they perfected, in a quantity and quality greater than anywhere else in the world, the printing and distribution of books. Against this background, by developing the imperial examination system to select candidates for the state bureaucracy, the Chinese rulers of the time were able to employ as bureaucrats those with outstanding intellect and talent. Because at the time the power of the state was a synthesis of rational administrative and financial management capabilities and military might, the civil service exam system was exceptionally sophisticated to the extent that it was unlikely that a better civilization would easily emerge. In Europe, it was still the Middle Ages, in which there existed neither printing nor the distribution of books. What if China had been interested in maritime expansion during this era? The compass, already invented in China, was likely being used for navigation during the Song dynasty.

However, the Song dynasty was easily destroyed by the northern China Jin dynasty (1115 - 1234) and then all too soon by the rising Mongols. During the reign over the land by the Yuan dynasty that followed the Song, twice the Mongol fleets were dispatched to invade Japan. The Yuan also performed military campaigns in Vietnam and Java. From this, we can understand that the Yuan was eager for expansion, but neither expedition was successful. During the reign of the Yuan dynasty, China was no more than one of the vassal states in which the administrative system was maintained, achieving no significant expansion or development. Eurasia is an interminably large continent; most likely, the Yuan, having obtained a huge territory and suffering from unlimited troubles at home and abroad, exhausted their energies in merely protecting it. They lost power in less than a hundred years.

However, during the Ming dynasty that followed the Yuan dynasty, particularly during the reign of Yongle Emperor, there was great zeal in exploratory voyages (into the South Pacific and Indian Oceans). By order of the emperor, the mariner, explorer, and admiral Zheng He commanded a large fleet that completed seven great maritime expeditions from 1405 to 1433. Zheng He spent almost his whole life sailing as a fleet commander. His fleet was comprised of 240 ships with a total crew of 27,000. In the Ming History, one of the Twenty-Four Histories (official Chinese historical writings), the largest ship he commanded was recorded as being 137 meters long, 56 meters wide and weighing 8,000 tons (according to the Wikipedia entry on Zheng He).

The tremendous scale of the Ming dynasty's fleet becomes obvious when we consider that Christopher Columbus' fleet was manned by about 100, and the ships were about one-sixth the size of the Ming's. This fleet visited various regions in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea area, and achieved a landing in the Indian city of Calicut (now known as Kozhikode) more than 90 years earlier than the 1498 landing led by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. On their fourth voyage, Zheng He and part of his fleet sailed to the east coast of Africa, presently around Kenya.

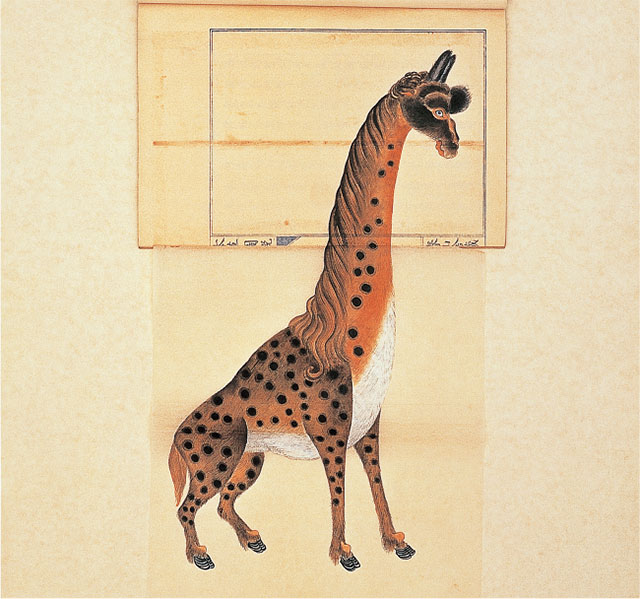

However, the purpose of the Ming's voyages was to demonstrate the wealth and power of the dynasty to distant countries and exact tributes from other rulers, not to plunder or exercise direct governance. In this tributary relationship was manifested the idea of Sinocentrism, whose aim was the establishment of a hierarchical relationship in which the dominant state neither interferes in internal affairs of, nor colonizes, a foreign country, but allows it sovereign authority in its internal affairs while creating a China-centered tributary trade. When the tribute was brought by the representatives from a vassal country, the suzerain country (Ming) would bestow a return gift several times to tens of times more valuable than the tribute. So we can assume that these voyages were not made as a way to profit from trade. It's heartwarming to find that, as China couldn't maintain the practice of offering such high-value return gifts, it instituted a restriction on tributes. It was likely difficult for China to preserve the dignity and honor of Sinocentrism. Therefore, it may be said that the maritime expansion carried out through Zheng He's great voyages were a maritime expansion with dignity and moderation. Among the items that Zheng He and his crew brought back were rare treasures from foreign countries as well as exotic animals such as giraffes, lions, ostriches and zebras, an equally heartwarming outcome.

Due to the control and restriction of Mediterranean Sea trade by Ottoman Turkey, Portugal and Spain, which had led the Age of Discovery, had no choice but to pursue maritime trade on other seas. Under the imperial order, ruffians were encouraged to "make a fortune in a single stroke"; it was maritime expansion that allowed the acquisition of riches and fame in exchange for a treacherous voyage in which men risked their lives. In other words, it was an audacious gamble in order to obtain national benefits. Preparing for voyages to secure ports of call and food supply points, as well as developing as-yet-undiscovered routes is serious business. We can imagine that this method naturally did not avert violent and aggressive urges.

What if China had made a series of voyages following Zheng He's path and eventually crossed the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa? What kind of world would we have today if the Ming's large fleet had discovered the Americas, circumnavigated the globe before the fleet of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, and proved that the earth is round?

Sinocentrism was not necessarily destructive. Therefore, although the Incan, Maya or Aztec Empires might have been asked to pay tribute to China, perhaps none would have been destroyed. And, what if an industrial revolution had taken place in China during the Ming or Qing dynasties? The world's wines might have featured labels covered in Chinese characters under a Chinese monopoly corporation operating in Europe.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

006

Asian setback

The fact is, China did not lead the Age of Discovery. The system of Chinese higher civil service examinations continued through the Ming and Qing dynasties, but longstanding systems and organizations necessarily contract systemic fatigue. It seems that, if we are to discuss without misunderstanding the knowledge that underlies the system of higher civil service examinations, they tended slightly toward the artistic and cultural, somewhat neglecting the practical sciences like engineering. The engineering revolution happened earlier in the West, where universities and libraries were established, education succeeded, and the rise of scientific knowledge thrived.

Even under the circumstances in which, Holland, England and then France, replacing Portugal and Spain, more carefully and beguilingly colonized India and East Asia, China, in a relatively stately and optimistic way, held fast to Sinocentrism. We should remember the China that, even as dynastic rule changed from Ming to Qing, had no other interactive relationship with, and was not accepted by, other countries save through the receipt of tributes. The position of Sinocentric civilization, which China had taken to be dazzling on blind faith alone, was gradually lost to the western Industrial Revolution, and Great Britain, which China confronted during the First Opium War, already had an armada equipped with cannons and steam engines. And as for trade, viewing Asia based on capitalist rationality, Great Britain focused on balanced trade among itself, India and China.

In an effort to balance trade, Great Britain, which, importing tea, porcelain, silk and other items, but exporting only very few, and thus had fallen into a trade deficit with China, decided to export to the Qing dynasty opium it acquired in India. Even after the Qing dynasty prohibited the import of opium, with the help of its military power, the British searched for and found a variety of other methods and routes to continue with the trade in China.

Had the United Nations existed at the time, and ruled on this state of affairs, surely it would have denounced strongly this coerced trade, in the context of opium dealing, as a threat to morality and peace. Eventually, Hong Kong came under British rule for years, and this course of events in history has had a strong impact in Asia.

Today, in 2019, I can't help but think about how this historical fact has complexly affected Asia, as Hong Kong's people protest their inclusion into the Chinese system. Just as colonial culture created the foundation of the tourism industry in Sri Lanka and Indonesia, Hong Kong, formerly governed by Great Britain, exerts a strange influence on the rest of Asia.

On one hand, Japan, which for over one thousand years has existed as a single country, and, isolating itself, sat all alone on the tip of East Asia, was extremely shaken by witnessing up close the First Opium War, in which China, so long deemed by Japan to be the strongest nation since the time of the Taika Reform of 645CE, fell too easily under military control of Great Britain. Japan was more sensitive than was the Chinese Empire to changes in the world around it, which meant it was more quickly affected at its center. Nagasaki, as a sensor, brought in information from overseas, and less than 30 years after the First Opium War, the feudal system characteristic of the shogunate and supervised by the samurai collapsed, imperial rule was restored, and the Meiji government was formed.

The policies laid out by the Meiji government, overly conscious of protecting Japan from foreign pressure, were extreme in their abandonment of their own culture and steering towards westernization. Simultaneously, Japan's government was so set on establishing itself as a modern nation that could stand shoulder to shoulder with the western great powers without being annexed by them that it became quite imperialistic and expanded outward.

As it was thought essential to develop industry through the proactive study of Western science and technology as well as political systems and to equip an army so as not to be easily invaded, Japan sent a delegation of government officials and exchange students to the west, Politics, economics, science, education, armaments, and so forth: the Japanese people were unusually highly motivated to learn about manifold disciplines, and Japan changed quickly, in a historically short period of time.

That accomplishment and efficiency were both on display during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5) and it seemed as if this island nation, positioned at arm's length from the world, had withstood the external pressure of the great powers of the world.

After that, two great wars shook the world. There were countless motives for war, but to put it concisely, the cause is likely the rapid spread on a global scale of the desire for statism and national enrichment. And its main characteristic was that the methods and technology used in warfare went through an accelerated change, and due to the introduction of new weapons (aircraft, tanks, poison gas, radar technology and so forth), there were mass casualties. In the last period of World War Two, nuclear weapons were utilized, and the world, having witnessed before its eyes, slaughter on an enormous scale, confronted the fact that the resolution of conflict through war leads to irreparable and devastating consequences.

Taking opportunity of World War One, Japan, recognizing that it had achieved its position among the great powers, superimposed the legitimate purpose of enlightenment of the people through modernism with that of enhancing national power, and eventually, the governors and diplomats were unable to control the military's aggressive decisions towards Asian hegemony, dispatching troops to and advancing colonization through Taiwan, Korea and Manchuria, China.

Imperialism or colonialism is the rampage of capitalist desires, brought about through the mechanism of the major western powers incorporating Asia, South America and Africa into their territories; if we question the immorality of colonialism, we must first focus our attention on how the western great powers viewed Asia.

On the other hand, if we take into account how the resilience of China and Korea towards imperialism or colonization had happened with communism and independence of ethnic groups underlying, we must recognize that the reason Japan continues to be accused of its colonial past lies in a deeply ingrained grudge against the fact that Japan alone, among all Asian nations, engaged in the same behavior as those western powers.

Japan from the Meiji Restoration to World War Two made its goal to count itself among the major world powers, and so it took part in colonial rule. But with its defeat in World War Two, it lost all rights as a colonizing force; the major cities were destroyed by air raids, 3.1 million people perished in the war, and with the dropping of two nuclear bombs, two cities were gone in an instant.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

007

Post-World War Two Japan and Manufacturing

If we reconsider tourism from an industrial perspective, we understand that its position in the world, or rather, its presence, must be taken up objectively, and updated. It's a little circuitous, but if we ask ourselves what are the future resources of Japan, it's essential that we calmly ponder modern history, so please bear with me for a little longer.

Having accepted the Potsdam Declaration and suffered defeat, Japan was in a wretched situation. The destruction caused by the aerial bombing was not confined to large cities like Tokyo and Osaka; provincial cities as well were wrecked by the frequent aerial raids. The nation was reduced to scorched earth. For seven years after the 1945 defeat, Japan was placed under the indirect governance of GHQ (General Headquarters), or Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. During that period, the Japanese government, with intervention from the United States, and oversight by the Allies' Far East Commission, settled a new constitution, which was proclaimed in 1946. The distinctive points included in this constitution are as follows: the emperor would not be the supreme influential figure, but simply a symbol; Japan would forever renounce war as a means of solving disputes, and that Japan would be a nation governed by civilians without any political intervention by military personnel.

In 1951 in San Francisco, a peace treaty recognizing the restoration of sovereignty to Japan and its people was signed by Japan and the Allies, going into effect the following year. At the time, antagonism between the Americans and the Soviets was becoming more pronounced, and a conflict on the Korean peninsula escalated into warfare between the forces of East and West. It's said that since all of East Asia might well be communized depending on the war situation, the United States had a strong ulterior motive to use Japan as a breakwater against the communist threat, or a bridgehead of the Western world.

In reality, Japan, an independent nation possessing no means of self defense, entered into the US-Japan Security Treaty and has accepted the US military presence in Japan. There came into existence an underlying structure in which although Japan was a sovereign nation, the United States would take care of military affairs. Herein lies the reason that both countries, Japan and the United States, continue to assert that this alliance is extremely important to the peace and security of all of East Asia.

The fact that mankind, having obtained the desperate armed force of nuclear power, uses war as a means of resolving conflict is a folly leading to the destruction of the human world. After the fall of the Soviet Union, it seemed that the tension between East and West might come to an end, but under the new circumstances of the rise of China, once again the world has regained that tension. The United States, in the context of its powerful military force and economic power, used to assume the role of police for itself and others, but in these circumstances is gradually losing any flexibility or leeway and on a grand scale turning sharply toward nationalism.

The posture of the United States, having become narrow minded and holding itself in high regard, is slowly but steadily influencing the world of the future in that direction. If rationality and objectivity take priority, and if humankind's wisdom functions vitally, in solving our many international problems, the stance that does not have military power deserves deep respect and pride, just as is written in the preamble to the Japanese constitution. However, in a world of growing uncertainty, in which the United States is so clearly turning toward nationalism, we must think carefully about how much confidence we can have in making the request, while assuming the sacrifice of American soldiers, that the United States defend the rest of the Far East. That is, reflecting on modern history, we must think about what kind of future vision we have, as a country that embraces its pacifist constitution addressing the principle of civilian control and the eternal renunciation of war as a means of resolution.

Let's return to the postwar period. After the Pacific War ended, Japan, now a scorched land, was driven by the manufacturing industry. In Japan, scarce in resources like oil or metals, its vision for efficiently reestablishing an economy was the import of raw materials and their export as products; perhaps it was a natural tendency that the processing trade, or industry, sprung up. Leaving security to the United States, the environment in which we could concentrate on industrial promotion and advancement became a tailwind for postwar Japan's industrialization and rapid economic growth. Japan's industry has evolved at an astonishing speed, resulting in a remarkable economic achievement by transitioning from the manufacturing and control technologies for airplanes and battleships to the production of a changing array of peaceful products, from textiles, to ships, to iron and steel and then to automobiles.

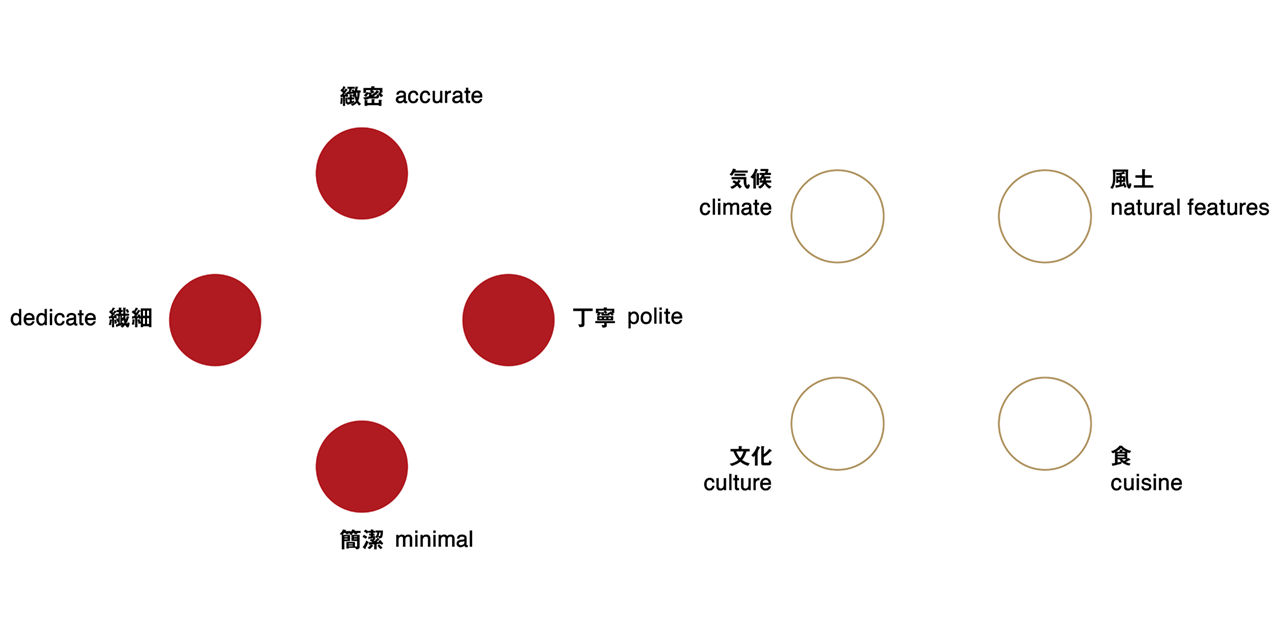

I can't assert the existence or nonexistence of national or ethnic traits, but the seriousness and scrupulousness of the Japanese certainly fit in well with the late 20th-century vision for industrialization: standardized mass production. It was an era when rational manufacture of hardware was blended with an acceleration in the precise control of production and compacting of products through electronics, and Japan's manufacturing tactics rode that wave magnificently.

In the early days, the manufacture of automobiles, which is the mainstay of the Japanese manufacturing industry today, slipped to Germany and the United States, but in terms of manufacturing methods, product quality and market creation, Japanese manufacturers have made steady improvement, and Japan's products had permeated the markets like water themselves, and at the end of the 20th century had achieved enough growth and refinement to drive the world's automobile manufacturing industry.

In consumer electronics and high tech equipment as well, our precise and compact electronic products swept the world, until Made in Japan became regarded as an indicator of high quality around the world. Japanese quartz crystal timepieces became known around the world for precision and luxury pricing, and our high-performing and reliable cameras gained great renown for their accuracy and exactitude.

In 1968, Japan's GDP was second only to the United States' and this island nation in East Asia became a solid world economic superpower. The price of land skyrocketed, and for a moment, Japan became drunk on its own economic prosperity.

But circumstances began to change, bit by bit. It has been claimed that Japan's stagnation has been caused by the bursting of the bubble economy, but it wasn't only that. The advances in computers as the technology that would reform manufacturing had already begun to transform the foundation of the next-generation industry, and Japan got a late start in industries that fused software, the Internet and data science.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

008

How we see ourselves

Just as was the case with the delay in achieving industrial transformation, there are things Japan should have considered, yet overlooked during the flourishing economy, like a vision of the future that included all of Asia, and an update of its own aesthetics.

The Meiji-era "performances" in which Japanese elites in Western gentleman-style silk top hats and mustaches attended dance parties night after night in Western-style homes may be necessary as a production comprehensively representing the power of an epoch-making civilization, and I do believe in their own way they had a meaningful effect. Whenever I see photographs or paintings of the Meiji Emperor attired in the official court dress of the Empire of Japan, consisting of European-inspired clothing, I imagine the infeasibility, difficulty, and tempestuous nature of the Meiji era. However, it would have been better if our devotion and commitment to the West had been limited to a short period of time. If Western civilization took the initiative to bring innovation to industrial science and technology, all Japan had to do was to learn that technology, but instead, we strove to conscientiously and carefully adopt everything, even including behavior and lifestyles. As Junichiro Tanizaki wrote in "In Praise of Shadows", during the Meiji Restoration, it would have been enough to study gas lighting technology, but instead, we embraced even the shapes and patterns of the Western gas lamps. As a result, Japanese culture lost the distinctive aesthetic that we had fostered and maintained within our way of living. It is not only Japanese sensitivity, delicate, nuanced and eclectic, that Tanizaki praises in this book; rather, behind the praise of shadows, he fervently expresses his nostalgic affection for the traditional beauty that was forgotten after the civilization and enlightenment of the Meiji era.

Of course, unlike consumer goods, culture can't be used up until it's gone. I believe culture is something that burns continually at the base of the sensibilities of those people who have inherited it, like a pilot light, and is like a gene that has the power to reproduce as long as one cares for it. The traditional Japanese cultural practices that may have seemed to lose their way during the Meiji era--architecture, garden design, painting and graphics, handicrafts, lifestyle aesthetics--are like the inheritance from our ancestors hidden away in the back of the family warehouse. I believe that the time has now come for them to be carefully retrieved, dusted off, and brought back out into the light in a global context. The day has come for us to identify resources that are rich and sparkling within our own culture and make use of them as resources for the future, while contributing to, and helping fertilize, the diversity of the cultures of the world (including the rest of Asia). That's my opinion.

I've written a little too much about the Meiji era, but the defeat in World War II was also a shock that defies description. Wartime education did not give the people room to think, but was used to turn everyone's attention, en masse, toward war.

In order for democracy to function well, it is postulated that all people are educated, improving their ability to think and make comprehensive judgments. From this perspective, we can identify not a few who felt the discomfort and resistance towards propaganda education, but under the abnormal circumstances in which military power dominated politics, the rationality of thought did not even function.

On the other hand, the American style engendered by Japan's defeat, the trend of enjoying freedom and individualism, appealed to the hearts and sensibilities of postwar Japanese as an intense counterpunch to wartime education. Japanese gradually became enamored with the United States, the country that delivered defeat to their own country. Young people in particular were greatly influenced by the United States, in music, fashion, lifestyle, life stance and values. Japanese who were raised as if the American culture that had spread everywhere before they were even conscious were their nourishment, experienced as annoying those traditional Japanese culture and customs that had been upheld from ancient times. Consumer culture and fads poured oil on the fire of the trend toward entrepreneurship that drove people to novelty or modernity, while the ancient or the aged were perceived negatively. Old Japan, with all of its accumulated history, was just about to be dismissed, along with the militaristic values of the pre-war and wartime periods.

Chapter 1 Focus on Asia.

009

What's opened up

On the other hand, among the Japanese, the admiration of, and devotion to, Europe was stimulated concurrently with their worship of the United States.

Because the Japan of the time, having suffered an enormous setback, was shifting direction toward recovery and restoration, it earnestly studied the European approach, which it greatly respected, and which was based on the logic of a continent that had achieved modernity first: an approach toward cities, the environment, economics, production and education. At the risk of being misunderstood, I'd say that in contrast with American culture, from which arose a powerful essence of epicurean tendencies animated by rising prosperity, Europe was brimming with the allure of diligence and authenticity created by the fusion of tradition and modern reason.

Germany, defeated country though it was, had steadily brought forth achievements of canny rationalism, such as the Bauhaus, which left its mark on pre-war art and architecture education, exercising a great influence on contemporary art; France, which by way of a popular revolution utilized and celebrated as national resources the historical assets created under the reign of royal families was admired by the world as a nation of art; Italy, brightly and positively forged forward in manufacturing products with uninhibited expression as found in the modeling that is characteristic of Michelangelo's work; England possessed superb traditions and knowhow regarding university education and continued to send out exceptionally talented people into the worlds of finance and economics: Matters we must learn from these European countries appeared one after another as if an enveloping fog had cleared, and Japan was once again motivated by an avid desire to learn more from them.

Freedom, pleasure and a daring attitude delivered through American culture energized the Japanese people, while the intellectual accomplishments of modernism we learned from Europe became the foundation of the significant development and growth of Japan's industry.

However, it's possible that our unquestioning adoration of the advanced Western civilizations that we assumed were the victors in our defeat has led to our disdain for other Asian nations. If we change our point of view and are able to possess a rationality that perceives the whole of Asia as a single "mother body", I believe we could discover the possibility of a productive future and industry.

By no means has the culture fostered and propagated in Japan been something brought about by modernism alone. We have learned much from continental Asia and the Korean Peninsula, and truly appreciated the awe-inspiring nature of objects brought in from these locations, but the culture of the Japanese archipelago came about through our consideration, contemplation and incorporation of these things over long periods of time.

Paper and written characters were introduced from the continent. Since ancient times, over a long period of time, we have learned from, and been taught by, China about law, the art of war, ethics, philosophy, tea, literature and the aesthetics of calligraphic works and paintings. The Japanese people have been inspired and influenced by the artistic culture of the Korean Peninsula from time immemorial, and even in today's Japan, such items as ceramics produced during the Yi Dynasty (1392-1910) are remarkably highly rated.

Today, East Asia has many problems that are difficult to solve. These are complex things that are not easily organized in a simple diagram, like an enumeration of historical facts or the ideological conflict between East and West. Rather than being extremely aware of our neighbors and overly concerned about the borders between us, at the very least in the realm of imagination that focuses on culture, the creativity to tear down the borders may be necessary.

From a global point of view, the world today is unstable, wavering. Individual people's movement over the face of the earth, transcending borders, is becoming increasingly dynamic. Nonetheless, precisely because of this state of affairs, attention is placed on local values and merits. The economy is the global guide, and precisely because of that, it becomes clear that the source that creates value is culture, i.e., the localities. This is because there is no such thing as a global culture. Culture is the inherent nature of the local itself.

Just as European colonial rule brought an awakening to Indonesia and Sri Lanka to the fact that they could offer as "value" in an international context what was all around them, isn't it necessary for East Asia to bring forth, through collaboration and response, its value in a global context? To this effort the mutual understanding and liberal education concerning East Asia's culture is indispensable. Liberal education, or refinement, or culture, is not the strategic cleverness to promote benefits for or guide profits to one's own country, but rather "intellectual openness".

In the case of "East meets West", "East" refers not to one's own country, but by necessity must refer to all Eastern countries. If we look at this as an entire Asian cultural sphere transcending nations and regimes, it is there that we must find the pulse of all of East Asian culture, which must continue to flow torrentially even today.

When I reflect on the Japanese archipelago, which, through an economic and industrial stagnation that has lasted 30 years, there has been a shift from a period of growth to one of maturity, I sense a gradual rise in the tendency to apply the above-mentioned viewpoint to the world. Not as a prosperity-crazed nation with a rapidly rising economy, but positioning our viewpoint on a past time, one thousand and several hundred years ago, and anticipating a time about fifty years in the future, what kind of Japan, what kind of East Asia and what kind of world will appear? Aren't the wisdom and behavior that quietly bring balance to the world required of Japan, from both outside of and within Japan, the cool place that is in no way in the center of the world, an archipelago at the Eastern tip of Eurasia? Today, when AI has begun to change the world, and the future is not easy to predict, the inspiration for that vision and possibility has begun to emerge in considerable force, with young people at the center.

Chapter 2 Thinking at the East end of Eurasia.

Chapter 2 Thinking at the East end of Eurasia.

010

Spices: Accentuating distinctive charms around the world

When I was 20 years old, I set out on a worldwide trip for the first time in my life. I bought a one-year open ticket with Pakistan Airlines, and first entered London via Beijing and Rawalpindi. Then I went on to France, Switzerland, Italy and Germany. After that, I flew to Greece via Yugoslavia, and stayed for a while on Mykonos, then crossed over to Egypt. From there I flew to Pakistan and then entered India over land. Although this was a typical itinerary for young backpackers, from it, I got some sense of what the world is like.

One of the things I remember from time to time is the flavor of the ham and sausage I ate in Frankfurt at that time. I'd had no plans to go to Frankfurt, but because of mechanical issues, the plane bound for Paris from London stopped for a time in Frankfurt, and the airline provided eligible passengers with a free overnight stay in a hotel, a blessing I never had thought possible on my frugal backpacker's budget. But what surprised me most was the taste of the ham and sausage served at breakfast the next morning. Up until then, I had thought ham to be the cylindrical sliced product offered by Japanese companies. However, among the idiosyncrasies in color, shape and texture of this Frankfurt meat that differed from the fresh, uncomplicated Japanese product, what surprised me most was the overwhelming spiciness.

In a junior high school world history class, I learned about the mysteriously named East India Company. It is an historical fact that Europeans, in the pursuit of spices, silk and other goods, opened Eastern marine trade routes, colonized Southeast Asia, established a corporation, and loaded great amounts of spices on ships bound for Europe, creating vast wealth. To a boy not yet in his mid teens, however, it was utterly incomprehensible that spices like pepper, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg could engender such enthusiasm among Europeans, giving them the determination needed to set forth in raging waters to obtain them.

To be honest, even though I experienced this spicy ham in Frankfurt, at the time I didn't fully realize what it meant. Later on, while traveling all over the world, I began to understand, though vaguely, what kind of values had swept across the globe throughout history. As I have experienced European cuisines, I have come to more fully understand the European fascination with pepper with each shake from a generously operative pepper shaker and each turn of a considerably large pepper mill, either of which is placed upon the table without exception. Certainly I cannot help but feel rather bleak thinking of the European meat culture in the time before the Age of Discovery when only limited amounts of spices, transported over land, were available. Pepper cannot be underestimated. Such is the power of pepper.

On the other hand, chili pepper was not available in Asia. Native to Peru in South America, it came into European hands through Columbus' discovery of the Americas, and from there, was brought to Asia. Today, we think of the spiciest foods as being from around Szechuan, Hunan and Yunnan in China, or India or Thailand. Coming to mind are the deep red Szechuan hot pot, boiling like the cauldron of hell, into which go chili pepper and Sichuan pepper; Indian curry, made of the many-spiced garam masala and Tom Yam Kung, with its mixture of painfully spicy chili peppers and sour lemongrass. But although just writing about these makes my tongue sting, it seems that inland China, India and Thailand were some of the latest places in the world into which chili peppers were introduced.

Even if we're talking about the same spices, there is a variety of spiciness. Pepper has a spiciness we'd call "sharp", while the spiciness of Sichuan pepper rather painfully numbs the tongue, and we'd call the chili pepper's spiciness "hot". It's truly surprising to find that chili pepper was brought from Latin America, and so before the Age of Discovery, there were no fiery hot spices in China's Sczechuan area, India, or Thailand.

interchange of things that don't exist in one's own culture. The world's interchange does not lead to homogenization by blending. Instead, the introduction of chili pepper intensified the individual characters of India's masala and Sczechuan's hot pot. Frankfurt's ham and sausage, too, matured into an essence of food indispensable to the life of the people thanks to spices brought from Asia.

I think that not only food culture, but all culture is the same. Indochina, Indonesia, and other former European colonies display unique maturity due to the import of European cultures, technologies and appetites. This can be said of Bali in Indonesia as well as of Sri Lanka.

The intercultural catalyst, or "spice" for Japan was first European culture during the Meiji Restoration, and then, after World War II, American culture, just as I've written previously. Next, regarding tourism, so important as Japan's future industry, what will become the catalyst that will intensify Japan's individuality? I believe it will be the value system known as luxury.

Chapter 2 Thinking at the East end of Eurasia.

011

What is Luxury?

From ancient times through the Middle Ages, at the pinnacle of the value system was the king. Although I feel reluctant to discuss this grand, yet rigidly conventional, theme, because I think that it's necessary to consolidate the history of values in order to consider the future of global tourism, I shall attempt here to lay out my interpretation of that history in broad strokes.

We can imagine that in order to command a huge community of people who could be identified as a nation, a terrific strength, a symbol of absolute order, which no one could refuse or repel, was needed. That is to say, kings came about because they were necessary. Even if the circumstances of the beginning of royalty were things such as individuals who were wise and excelled at martial arts won multiple battles and wars, commanding others and reigned at the top, as a consequence, the symbol of the king became more important than the actual faculties or abilities of the king in societies of ancient times and the Middle Ages. And to be completely direct and honest, while a wise and great royal leader was ideal, despots, fools, those of tender age, and even "emperors wearing no clothes" served the purpose just fine. Because conspicuous authority is the cornerstone of the value that can support a huge group of people, as long as there is a symbol that can represent such authority, a royal ruler appeared as such, and could convincingly conduct him- or herself as a monarch. In other words, the ruler could function as a ruler. Very clearly, rulers were symbols.

For example, bronzeware pieces from ancient China are densely covered with complex patterns. Confronted with the dispirited air of such a piece, completely covered with verdigris rust, one cannot help but consider the length of human history, and yet that complex and all-encompassing pattern exudes an indescribable and mysterious aura, and a magnetism. That is, I would say that the symbol represented as dense patterns suggests the ruler him- or herself.

Bronzeware, when first created, would surely have had the power to overwhelm those who saw it, like a shiny new coin. These pieces are said to have been ceremonial items, used in rituals, but no matter the type of rite, surely they functioned as symbols of great power. Signifying a tremendous achievement that could never have been made without massive investments of time and energy by highly skilled individuals, the imposing appearance of these pieces must have made ordinary people gasp in awe and reverence.

Decorations and ornaments used in the country that sees itself as China, which upholds the way of thinking that assumes Chinese cultural superiority, not limited to bronzeware, were packed with magnificent patterns representing the dignity and majesty of monarchs and rulers. Complex patterns also appear in other regions where there are dominant powers. For instance, the Taj Mahal, the tomb for the wife of Shah Jahan, India's Mughal Emperor, is covered in intricately patterned stone inlay, comprised of many colored stones from around the world. And in the Islamic world, the inner and outer surfaces of the mosques are crowded with dense geometric patterns; the tremendousness of that density seems to embody the authority of Islam. In a way, it's as if the impression goes beyond beauty, and one feels intimidated. Dense patterns might have been, in a sense, a show of force that functions as deterrence to war, since they indicate a menace that can be sensed from something like a full-body tattoo, as if declaring, "defiance will bring dreadful consequences."

In Europe as well, during the era of the absolute monarchy, baroque and rococo styles, featuring exceedingly intricate ornamentation were devised, as dazzling adornments for royal authority. The Christian Church, a symbol of faith, also had to continue to exude a majestic air of holiness and dignity as a representation of religious precepts and morals, and an enormous amount of energy was invested in the magnificent Gothic edifice. As for the chairs in which royalty and titled nobility would sit, which boast the "cabriole legs" with curves and various details, we would be better off considering them as symbols hinting at the height of a throne than as contraptions for sitting.

Admiring royal palaces, proud of churches, inheriting as items inspiring pride interiors and furniture covered in ornamentation, people have tried to share in authority by inserting into their daily lives those patterns or replicas of those items. In the long history carved out by monarchs and countries, the implicit preference for valuing luxury has gradually been etched into people's world views, developing and growing, just as calcareous water dripping over time forms a limestone cavern.

Of course, from splendid ornamentation, refinement and restraint also came about, and the modesty known as elegance came as a derivative as well, but the adoration of the common people tended towards the radiant ornamentation at whose pinnacle was the royal palace. Even today, when the governing power of the monarchy is purely symbolic, and even ordinary people have become the star actors in their own lives, people's longing for luxury remains firmly rooted.

Chapter 2 Thinking at the East end of Eurasia.

012

Classic and Modern

As the era of monarchies largely came to an end, the world shifted to modern societies, which emerged through the form of popular revolutions in the West. This marked the arrival of societies in which the center of value was not the monarch; instead, common individuals played leading, active roles. When we consider that the French Revolution broke out at the end of the 18th century, we recognize that this is not ancient history. Rationality developed and prevailed, spreading throughout society, and a distinct way of thinking arose in which waste and excess were eliminated from the production process of architecture, furniture, daily necessities, and so forth, guided by a clear concept that it would be best if material, function and form were connected as closely as possible. This is modernism.

Architecture, interiors and furnishings that had served kings and aristocrats became supple and free, with innovative molding and design perspectives born from the movements of Art Nouveau, Futurism, Secession, De Stijl and Bauhaus. And beheld in spaces created by representative modernist talents such as Le Corbusier and Mies Van der Rohe, was an aura of the radiance of reason, emancipated from authority and style.

Meanwhile, there were not only popular revolutions but also successive technological innovations that came to be known as the Industrial Revolution, resulting in the temporary concentration of worldwide wealth in Europe and North America. The new masters of luxury were not royal rulers but industrialists and the wealthy. In Japanese, we have the word narikin (成金); when ordinary people obtain great riches through hard work and good luck, they invest their wealth only in building themselves grand and luxurious residences. The word comes from the game of shogi, a kind of Japanese chess (the board game of generals), in which a foot soldier (fu-歩) is promoted(naru-成る) to gold (kin-金), referring to the attitude of the nouveau riche, who behave as if they had always been members of the upper classes. In any case, the term is nuanced, suggesting ridicule of this newly enriched class' appetite for luxury. In short, while the mechanism of society has been updated, it seems that the former adoration toward authority, deeply rooted, remained. The masses, while coolly observing the mad pursuit by the wealthy class of luxury as a symbol of royalty, seemed to have secretly harbored a respect and honor of authority, as a value that cannot be easily gained by wealth alone.

If it could be said that we humans survive based solely on reason, perhaps the wave of modernism could have been expected to cloak every single environment. And yet there's something I feel deeply when visiting European countries. I find high tech cities lined with skyscrapers offer a comfortable environment, but at the same time, I think that perhaps the very center of value still remains in their old quarters, which have been preserved throughout the ages.

The church steeple shoots skyward in the center of town; the castle of a lord who has long managed the region with order and discipline functions as the area's heart; commoners, who have willingly accepted the system, work to create their own housing, public square, market and entertainment quarter. Into anything that has lasted for a long time is integrated human wisdom that has been devoted to supporting the community's sufficiency and daily life all for all that time; perhaps people can not simply resolve to utilize reason to update these kinds of things. Therefore, the inclination toward classicism runs deeper in people around the world than we might imagine.

The enormous Milan Furniture Fair (Milano Salone) is held every year. As a designer, I have had many opportunities to attend, lured by new design trends, but even at this cutting edge event oriented toward the novel, the majority of the pieces filling the gigantic exhibition space are classic, or evoke classical style; there are not a great number of purely modern items unfettered by classicism. Because furniture fairs target large-scale demand such as that from new hotels around the world, naturally that trend reflects the conservative preferences of the world's hotels.

After the emergence of modernism, its ideology sprouted and spread in design through Germany's Bauhaus. Since then, rational thinking with regards to Umweltgestaltung (environmental design) spread rapidly around the world. And yet the longing for abundance and luxury is still conservative. This trend is conspicuous among the rich in particular.

It seems to me that when capital and wealth became available to more people around the world, the symbolic nature of the royal palace was transferred to the stately mansions of the rich and high-end hotels. At the latter, weddings, banquets and parties are held on a daily basis, in which they function as the joyous settings for the enjoyment of fine drink, gourmet food, high fashion and celebratory social interaction.

Ordinary people come to these places to enjoy ceremonial moments; the rich want to possess them; those who honor aesthetics come to wish they could create them.

Chapter 2 Thinking at the East end of Eurasia.

013

Why Japan's Hotels are European-Classic Style

It's probably unavoidable, and natural, that Europeans consider the tastes of former kings and nobility as traditional, and feel towards them both yearning and nostalgia. However, looking back on Japan, I wonder why all of our famous hotels appear to lean in a similar direction.

There are several possible reasons. First, in Japan, it was thought that in an international arena, highlighting the culture of one's own country is not elegant in the least; it would be rather annoying to visitors from abroad to be exposed to our particular cultural tastes and values without taking into account the cosmopolitan atmosphere. Because hotels representing one's country are expected to provide for universal social rules that allow guests from across the world to enjoy a stay without any sense of unease, it was thought that we could not demand that they remove their shoes at the entrance or sit on a zabuton cushion on a tatami mat floor. The purpose of hotel services is to allow guests a relaxing and comfortable stay. It would be boorish and insensitive to impose unnecessary tension by insisting on the reasoning that, "It's Japanese aesthetics". There is also the opinion that it is a virtue of modesty to welcome and host guests according to the manners of their home countries.

Another reason can be imagined. Perhaps hotels in Japan, by learning how to treat visitors from abroad, have acted as role models, educators, if you will, to help the Japanese comprehend and assimilate Western culture. Japanese people have considered it shameful to not be familiar with [Western] table manners, including the proper use of silverware. Whenever I recall my embarrassment concerning manners that differed from the culture in which I was born and raised, whether sipping soup without making any noise, or using a napkin during the meal, or how to pour wine, I cannot help but recognize the educational role played by Japan's international hotels.

That is, it has been both the mission and the premise of Japan's high-end hotels to present and perform Western ways flawlessly and in a sophisticated manner, leaving aside Japanese ways. These included not only table manners, but also the appropriate preparation and wearing of clothing according to seasons and occasions, the manner appropriate to the holding of ceremonies and parties, Western manners and deportment and the request and receipt of service; most surely, there should have been a vast diversity of directions. With this culture and thinking so deeply ingrained, the ways of Japanese hotels will not change easily. This is not because they are pandering to Western classicism, but rather because they continue to function in this role.

Nonetheless, when you visit any country, any cultural sphere, what ignites people's hearts and inspiration is when you are welcomed with the essence of that country and its culture. Even though the West holds the historic predominance of earlier modernization, when civilization reaches a level of equilibrium, individual cultures naturally line up equally, each exhibiting its own uniqueness and individuality while making the world shine richly. There is something heartwarming in the attitude of humbly presenting one's home culture to the world, with this understanding.

Thinking about these things, and reflecting on the traditional Japanese ryokan that maintains a special atmosphere and appearance, I could not suppress something like a strange desire or ambition gradually bubbling up from within.

If possible, I want to polish, and then quietly, yet with adequate preparation, to present to the world a unique cultural ingenuity nurtured in an island nation on the Eastern tip of Eurasia, one existing nowhere else in the world. And in Japan I want to soberly present cultural diversity as a contribution to the world's abundance.

The Meiji era should be able to be considered part of the distant past. Certainly the Westernization movement of that era, like the descent of a massive meteorite, was a violent shock for Japan, and its lingering effects are still felt today. Even as we gaze at the court costume worn by the Emperor and the royal family during ceremonial events, we recognize that for the nation of Japan, Meiji has already become an established part of our tradition. But Japan and the world are changing. Industry also faces a critical juncture of a great transformation. It seems a good time to awaken from the unconsciously imprinted adoration of Western cultures.

If hotels perform the function of cultural education, I would like them to become places of the teaching of not Western, but Japanese, culture. This is not for people coming from abroad, but for Japanese people. Among the Japanese, the consciousness or awareness of Japanese style is already becoming diluted, and they are losing a sense of pride in its uniqueness and in hosting the world by its means. Under these circumstances, I think it would be interesting if the Japanese-style hotel were to come on the scene, with a stimulating effect.

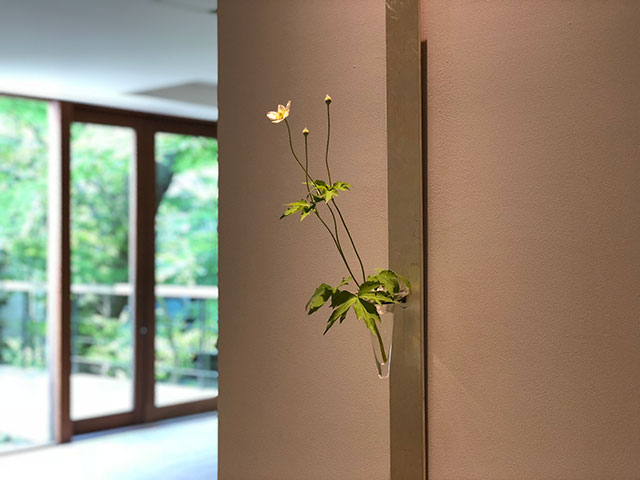

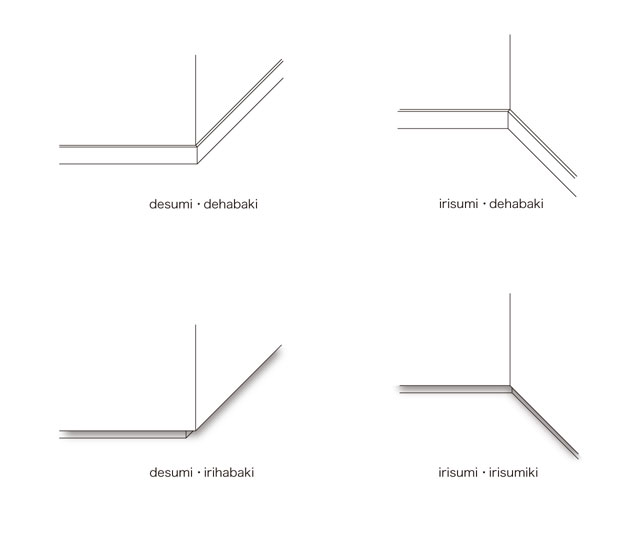

I propose that we must not settle for superficial interpretations confined to conventional Japanese stylization of interiors, furnishings, textiles, ornaments and decorations. Rather, as a prerequisite of allowing for the comfort of guests from around the world, Japanese aesthetics should be injected, without hesitation, into every conceivable spatial language involving the design and construction of architecture, in relation to the land and the natural environment, and the base language that forms both guest rooms and the hotel itself; specifically speaking, this ranges from the rooms' bedding and tables, sofas, baths and washstands, to common-use areas such as lobbies, banquet halls, restaurants, libraries and spas. It goes without saying that this must also be said about the etiquette of hospitality.

Now, more than ever, proceeding from the thinking that it is rational to make noise while slurping soba, it has become possible for us to explain this proactively to people from other countries. It's also taken a little time to explain that one eats nigiri zushi with one's hand. Perhaps in the same way, hotels have also begun to change, slowly, one little example at a time.

Chapter 2 Thinking at the East end of Eurasia.

014

Schindler House

We often hear the story of how the founder of the Bauhaus movement, architect Walter Gropius, and his contemporary, architect Bruno Taut, gained fresh inspiration from Katsura Rikyu and other examples of traditional Japanese architecture. However, it seems that their praise was somewhat disagreeable to the contemporary leaders of the Japanese architecture world.

This is because even if Japanese architecture had not been expressly evaluated by way of Western modernism, the modernists of Japan who drove the architectural world at the time took pride in the fact that Japan was an architectural mecca, and a treasury of architectural resources that could contribute to the richness of the world. When I read this anecdote somewhere, and thought to myself that it might be right, I felt that I understood; even without being unduly praised by people from other countries, Japan has not lost sight of itself, completely engulfed in a wave of Western culture. That rationale would probably naturally manifest upon the increase of national power and economic maturity.

However, upon reconsideration, it seems to me that Taut, Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright were struck, refreshingly, by Japan's traditional architecture, but what they recognized may have differed slightly from the Japanese originality that our domestic architects pondered.

After the Meiji Restoration, Japanese architecture carved out a history of continual confrontation with modernism. Unlike today, with its nimble architecture, in an age when architecture was spoken of as taking responsibility for the nation itself, I wonder what kind of complications were involved in the act of working as an architect while being aware of the rivalry between tradition and Western modernism. There were many, many Japanese architects who, while avidly studying the trends of the modernist wave and those of Western modern architecture, with an eye to Japan's identity, were also exploring paradigms for original and distinctive architecture. Following the Meiji Restoration, these many architects had no choice but to play the role of building Japan's vision into their body of work.